We’ve recently developed a new tidal model for the Straits of Gibraltar. This model will benefit all sorts of users but primarily commercial vessels heading into and out of the Mediterranean.

There are many elements that contribute to the complexity of tides and currents around this narrow inlet. So here we explain why the currents in the Strait of Gibraltar so complex.

PASS THE SALT

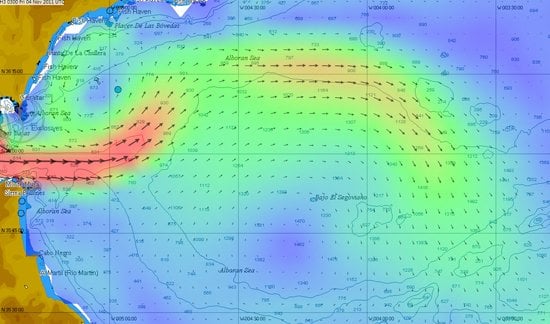

Currents through the Strait of Gibraltar are mainly caused by an exchange of water of different salinity (saltiness) between the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. The water in the Atlantic is less salty and less dense than water in the Mediterranean and it flows eastwards into the Med through the Straits as a surface layer, about 125m deep with a speed of two to three knots.

To make things more complicated, superimposed on these density-driven currents are tidal flows that can reach four knots. The tidal flow will either speed up or slow down the eastern flowing current, depending on the phase of the tide.

Furthermore, close to the African continent there is often a narrow counter current (i.e. out of the Mediterranean) of two knots.

As the current flows eastwards it interacts with the Camarinal Sill (the shallowest part of the Strait) and this causes 'internal waves' – a vertical motion between the two layers of 50-100m with a wavelength of two to four km which can be seen as a surface wave pattern that can be detected by satellites, radiating eastwards from the Strait.

THE ALBORAN GYRE

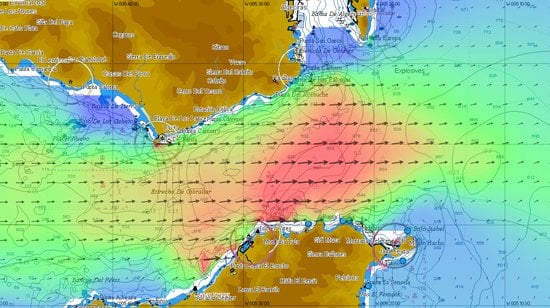

As the upper level flow pours into the Mediterranean, the Coriolis force (an effect of

the earth's rotation) causes it to form a large clockwise eddy (gyre) off the North African coast called the Alboran Gyre. A smaller weak anti clockwise eddy forms to the North. Counter currents (westward flows) can be seen close inshore along both shores, particularly near headlands that project into the current.

The western end of the Mediterranean, the Alboran Sea, is the habitat for the largest population of bottlenose dolphins in the western Mediterranean, is home to the last population of harbour porpoises in the Mediterranean, and is the most important feeding ground for loggerhead sea turtles in Europe.

A layer of out-flowing dense water stays deep after exiting the Med and forms a ribbon extending along the Spanish and Portuguese coasts at about 1000m depth. It splits into two, at Cape St Vincent, with one branch going west and the other branch going north. Evidence of this flow can be seen as far north as the Greenland-Scotland sill.

Amazingly, the westward flowing Mediterranean water reaches the American continent and travels south to be found in Antarctica and the Weddell Sea.

Information about currents in the Straits of Gibraltar has been kindly provided to Tidetech by the University of Cadiz.