Whatever craft you sail, currents can have a significant effect on your transit times across an ocean, particularly where the major ocean currents such as the Kuroshio and Gulf Stream flow. However, the beginning and end of most ocean crossings transit coastal waters, where there can be strong tides. Understanding how and why each type of current forms and where they occur increases the likelihood of a successful passage - whether it be a 'just-in-time' arrival on a ship or a podium finish in a yacht race.

Understanding Ocean Currents

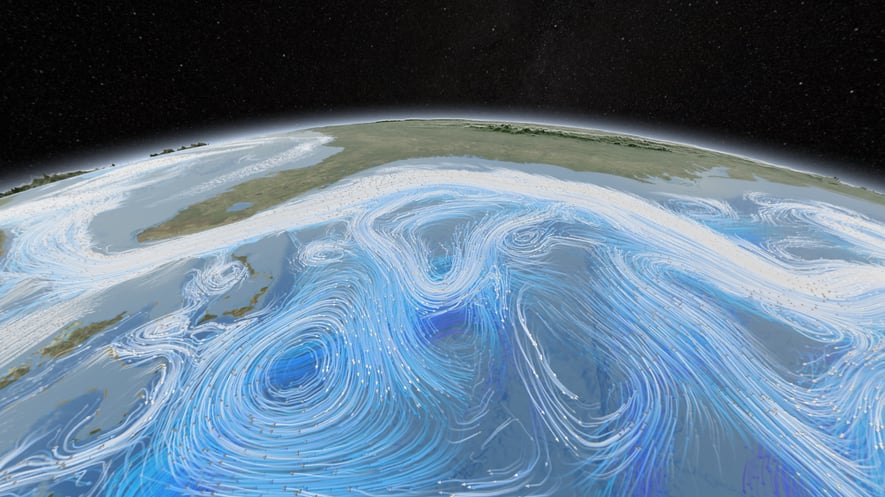

In the deep ocean (water over 300 metres of depth) the currents are usually in a reasonably steady state, changing slowly over several weeks. Some areas are more dynamic, such as the Gulf Stream east of Cape Hatteras, and the Kuroshio Current in east Asia. Even in their most volatile states, these currents only change slowly from day-to-day, a feature amply illustrated in the video below from NASA which shows how the deep ocean currents change around the world, over a two year period (note the timeline top-right).

Changes are driven by:

- the friction from winds blowing on the ocean's surface and

- changes in density and salinity between adjacent parts of the ocean, a force known as thermohaline circulation.

"The conveyor belt begins on the surface of the ocean near the pole in the North Atlantic. Here, chilled by arctic temperatures seawater gets even saltier, because when sea ice forms the salt does not freeze and remains in the surrounding water. The cold water is now more dense, due to the added salts, and sinks toward the ocean bottom. Surface water moves in to replace the sinking water, thus creating a current." - oceanservice.noaa.govt

You can view a video of this process in action courtesy of NASA, below;

Note that ocean circulation is three-dimensional, and the thermohaline circulation can't occur easily in water depths of under 300m, where the ocean floor rises to the land to form an area known as the continental shelf. It is here where tidal processes are dominant and deep ocean currents fade away, (although there is some mixing between the two on and inside the shelf edge).

Typical Continental Shelf

Coastal currents

Tidal currents, caused by astronomical forces, are usually the dominant force on the continental shelf, although wind-driven currents also play a part. The degree to which one or other dominates depends on factors such as the size and shape of the shelf locally and the speed and direction of winds blowing across the sea surface. The frequency at which tidal currents change depends on where you are in the world - simplistically, shelf seas in the Atlantic Ocean experience two high and two low tides a day (semi-diurnal frequency) and in the Pacific Ocean one high and one low tide a day (diurnal frequency). Elsewhere a mixture of the two is seen. As tidal currents are inherently predictable, we can have a high degree of confidence in their speed and direction in advance.

We will be looking into the causes and phenomena of Tides in a lot more detail in future articles, but for this one let's look at a real-life example of how ocean and tidal currents co-exist in the North-East Atlantic, where the volatile Gulf Stream exits the US Coast to head East, and strong tidal currents are in play on the continental shelf in the Gulf of Maine. You can see how limited the interaction is between the two types of currents and how abruptly the picture changes between the shelf seas and the deeper ocean at the shelf edge.

The dataset shown is the first two days of our seven-day combined ocean and tidal current forecast. It’s these data, and other information, that we at Tidetech use to help many shipping companies to save fuel, reduce emissions and optimise their fleets; and competitive sailors to win races.

If you are interested to find out more about our data and how it can help you afloat or ashore, take a look at our catalogue of metocean data, here .