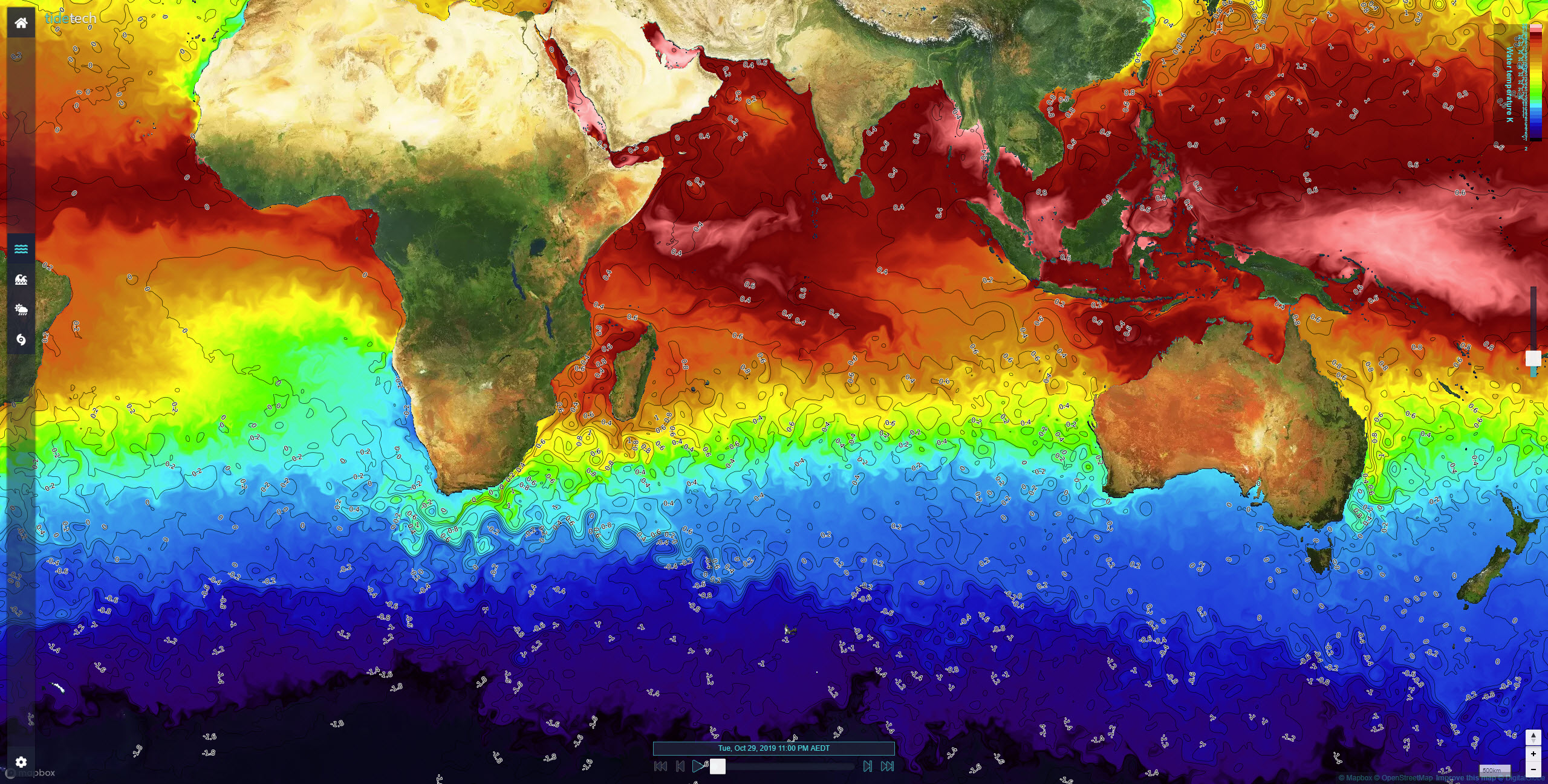

Sea surface temperature (SST) tells us a lot about the oceans. It can help pinpoint the exact position of currents and shows where warm and cold water meet at regions known as fronts or temperature breaks.

Fronts and the position of hot and cold water are of interest to offshore and ocean yacht racers because they show exactly where the strongest current is flowing and in what direction. Oceanographers use SST to validate ocean models.

Tidetech has sourced the best quality resolution SST (1.1km) from NASA's AVHRR GOES and POES satellites, which is available on a near real-time basis (depending on location). When the skies are clear, we can produce images of outstanding quality. Unfortunately, the satellites can’t see through cloud, so most images have some gaps in them. To help reduce the gaps we make composite images of several satellite passes – almost as good as the absolute latest data.

SST is a proxy for the current data. It shows the structure of cold and warm core eddies and is an independent way of verifying current data when overlaid together.

Current data is a large scale (15nm) resolution, but SST is 1km resolution, so can show detail of the structure of the current and position of ‘SST Fronts’ – sharp changes in temperature that are indicative of sharp changes in the speed of the current.

Localised wind differences in high-temperature areas

If you are sailing in an unstable air mass, it could be an area of water that is warmer than the surrounding water creating a mini low-pressure system. This is akin to a sea breeze where rising warm air sucks in colder air from further afield.

Small cumuli are often created and the breeze may become shifty both in strength and direction. It is often possible to spot where stronger warm currents begin by looking at the sky – colder water will exhibit clear skies above and warmer water will exhibit puffy clouds.